SMDOT è molto felice di annunciare l’inizio del suo quarto anno di programmazione presentando la mostra collettiva “SURFING ON THE ALGORITHMS”. Sette artisti italiani, Marco Cadioli, Alessandro Capozzo, Giovanni Fredi, Federico Poni, Eleonora Roaro, Guido Segni e Stefano Spera, hanno realizzato lavori inediti, o quasi, esplorando l’intersezione tra tecnologia e creazione, confrontandosi con un tema, uno strumento, molto attuale come l’intelligenza artificiale, e soprattutto con una sua parte fondamentale, quali sono gli algoritmi.

L’IA, fino a poco tempo, confinata nei laboratori di ricerca ha negli ultimi anni fatto il suo ingresso dirompente nella vita di tutti i giorni. Tutti sembrano ossessionati ed affascinati dal suo utilizzo e dalle promesse di crescita e sviluppo, che sembrano infinite, così come, dalle sue possibilità di applicazione in grado di utilizzare una tecnologia sempre più efficiente e pervasiva.

Il titolo di questo testo, “Né intelligente né artificiale” può sembrare provocatorio, in qualche modo potrebbe voler affermare, a priori, un giudizio negativo nei confronti della tecnologia, della AI e degli algoritmi, ma in realtà è solo un’iperbole nella speranza di attrarre la vostra attenzione e posizionare lo sguardo da un particolare punto di vista.

Guardiamo queste macchine, questi software, spesso, con eccessivo incanto, affermiamo noi la loro intelligenza rispetto ai risultati che riusciamo ad ottenere. Restiamo sbalorditi dalle immagini che ci mostrano a fronte di una nostra richiesta avvenuta attraverso un testo, oppure alla stesura di uno scritto in relazione ad un argomento da noi indicato, addirittura alla formulazione di una poesia, di una canzone o di un brano musicale, sempre, rispetto alle nostre indicazioni. Cosa interessante, possiamo tranquillamente non essere soddisfatti e la macchina continuerà a cercare soluzioni per noi, senza mai stancarsi o quasi. Proverà sempre ad accontentarci. Le sue risposte saranno sempre verosimili.

L’Intelligenza Artificiale è la simulazione dell’intelligenza umana in macchine programmate per pensare e imparare come gli umani. I sistemi di intelligenza artificiale possono svolgere compiti come comprendere il linguaggio naturale, riconoscere immagini, prendere decisioni e risolvere problemi. Esistono diversi approcci, ma tutti implicano l’utilizzo di algoritmi avanzati e modelli matematici per elaborare e analizzare i dati. Alcuni dei principali approcci includono sistemi basati su un insieme di regole predefinite per prendere decisioni e risolvere problemi. In sintesi, l’IA è una branca dell’informatica che si occupa di creare macchine o sistemi informatici in grado di eseguire compiti che normalmente richiederebbero l’intelligenza umana. Utilizza algoritmi avanzati e modelli matematici per elaborare e analizzare i dati e fare previsioni o decisioni basate su di essi.

Questo significa che in qualche modo ci danno l’illusione di trovare soluzioni semplici ai nostri dubbi o aspettative, ma solo noi possiamo decidere se quelle soluzioni ci soddisfano o meno. La modalità di apprendimento di questi sistemi e il loro modo di corrispondere ai nostri desiderata si basa sull’inganno, un approccio molto comune tra gli uomini, ma anche tra gli animali e le piante.

Siamo abituati quotidianamente a convivere con quello che possiamo definire l’inganno banale, cioè qualcosa che sappiamo non essere reale, ma che in determinate circostanze, decidiamo, istintivamente, di ritenerlo come tale.

Possiamo dire che la storia del pensiero nasce, si basa, sull’inganno. Dai Sofisti alla metafora della caverna di Platone, dall’invenzione dei miti alle religioni, passando per l’invenzione della prospettiva, le varie scoperte scientifiche, la letteratura, l’immagine fotografica, il cinema, la pubblicità, le serie TV, i social media, Siri, Alexa, etc…

L’essere umano è sempre stato attratto dall’illusione e dall’inganno, fa parte della suo essere, della sua vulnerabilità, delle sue modalità di relazione e nello stesso tempo ha dovuto allenare e sviluppare tutte le sue capacità per potersene difendere, per cercare di scoprirlo in anticipo e non subirlo.

In qualche modo ritorniamo all’iperbole iniziale, il problema non è l’intelligenza artificiale e la sua capacità di poter progettare macchine capaci di performance migliori di quelle umane, con tutte le conseguenze negative e positive sulle abitudini umane e le implicazioni etiche e sociali, il problema è sulla nostra capacità e volontà di distinguere tra gli umani e le macchine. Rifiutarsi di interagire con l’IA non è possibile, ma possiamo resistere. Possiamo stare in equilibrio, come quando si surfa, tra la nostra capacità di utilizzare con profitto gli strumenti che ci vengono messi a disposizione utilizzando l’IA e quello di adottare un atteggiamento informato, critico, scettico, creativo nei confronti della stessa. La sfida è quello di diventare utenti sofisticati.

Confrontarsi con l’arte, con le opere d’arte può essere un ottimo esercizio per non rinunciare alla complessità, alla ricercatezza, alla difficoltà, all’insoddisfazione.

“SURFINF ON THE ALGORITHMS” è da questo punto di vista una mostra sofisticata, complessa, scomoda, ogni singolo lavoro è una soglia di senso per il guardante, ogni lavoro porta con se molte domande, ogni lavoro è mancante, mancante di una risposta definitiva pur nella sua definizione estetica. Il piano concettuale che unisce tutti i lavori è la ricerca sul tipo di immagini che stiamo producendo nel contemporaneo, grazie anche alle nuove tecnologie, e quale rappresentazione della realtà vogliamo costruire con esse.

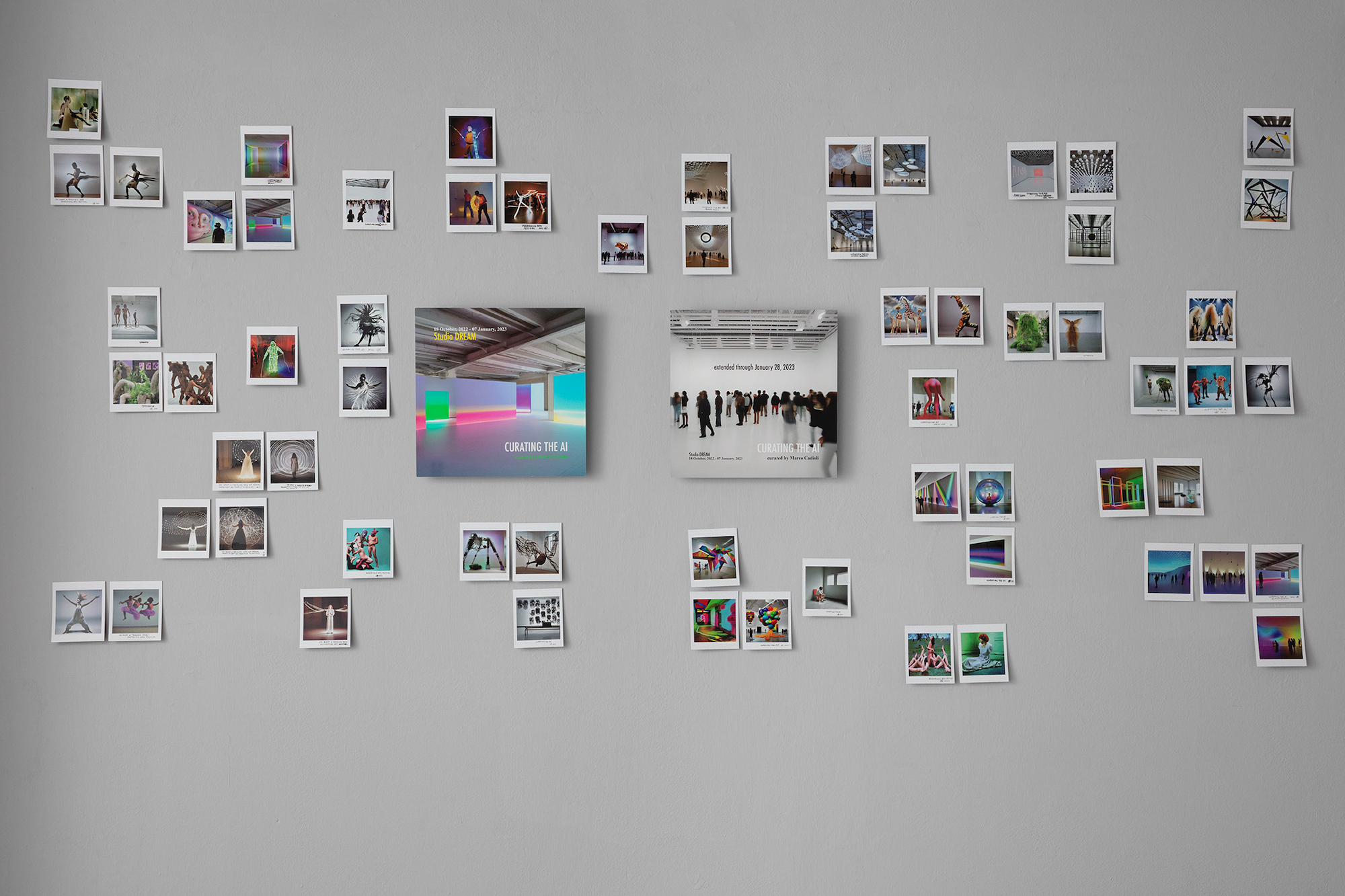

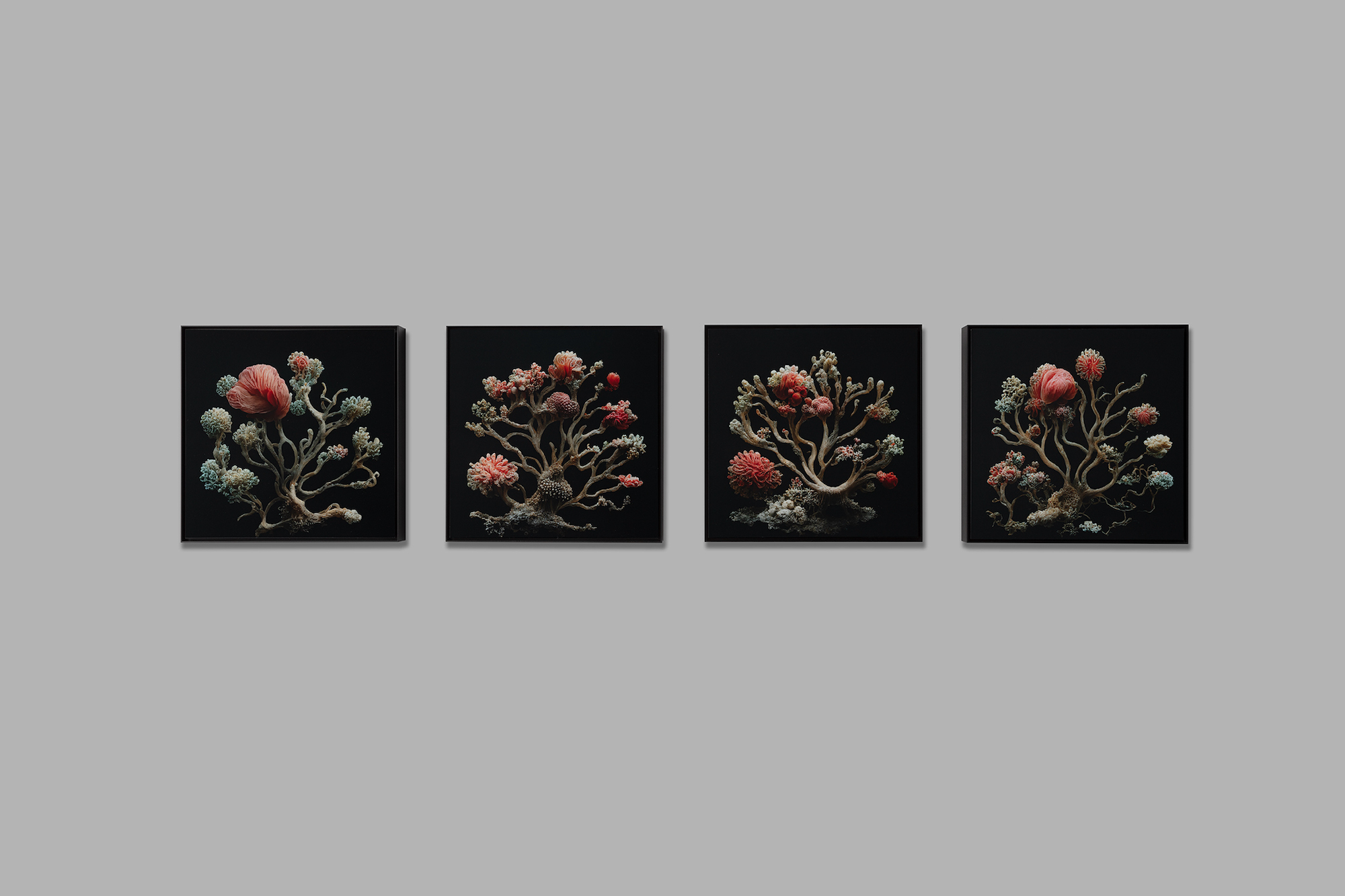

Marco Cadioli con l’installazione “CURATING THE AI” grazie all’utilizzo di un programma basato sull’IA, ha generato la documentazione di una mostra d’arte, con artisti, opere, evento di apertura, eventi performativi e culturali, spettatori. Tutto documentato e messo in rete, con la soddisfazione del pubblico, curatori, critici, artisti, con alcune delusioni per non essere stato invitati. Ha generato un inganno banale. La documentazione della sua mostra, grazie a stampe digitali su dibond e polaroid (digitali), partecipando come opera d’arte alla collettiva, diventa una performance avvenuta in un altro tempo ed in un altro spazio, diventa una meta-mostra, oppure una meta-opera. Cambia la figurazione cronologica del tempo. Una sorta di futuro anteriore. Un futuro nel passato che ritroviamo anche nei lavori di Alessandro Capozzo, “Chimera I, II, III, IV”, dove siamo attratti da immagini che sembrano arrivare da un museo di scienze naturali del passato, oppure da una wunderkammer di un collezionista del XVIII secolo. Immagini liriche, verosimili, che ricordano tratti di piante ed animali, senza essere né l’uno né l’altro, ma nello stesso tempo dando una rappresentazione metafisica di elementi passati che arrivano dal futuro.

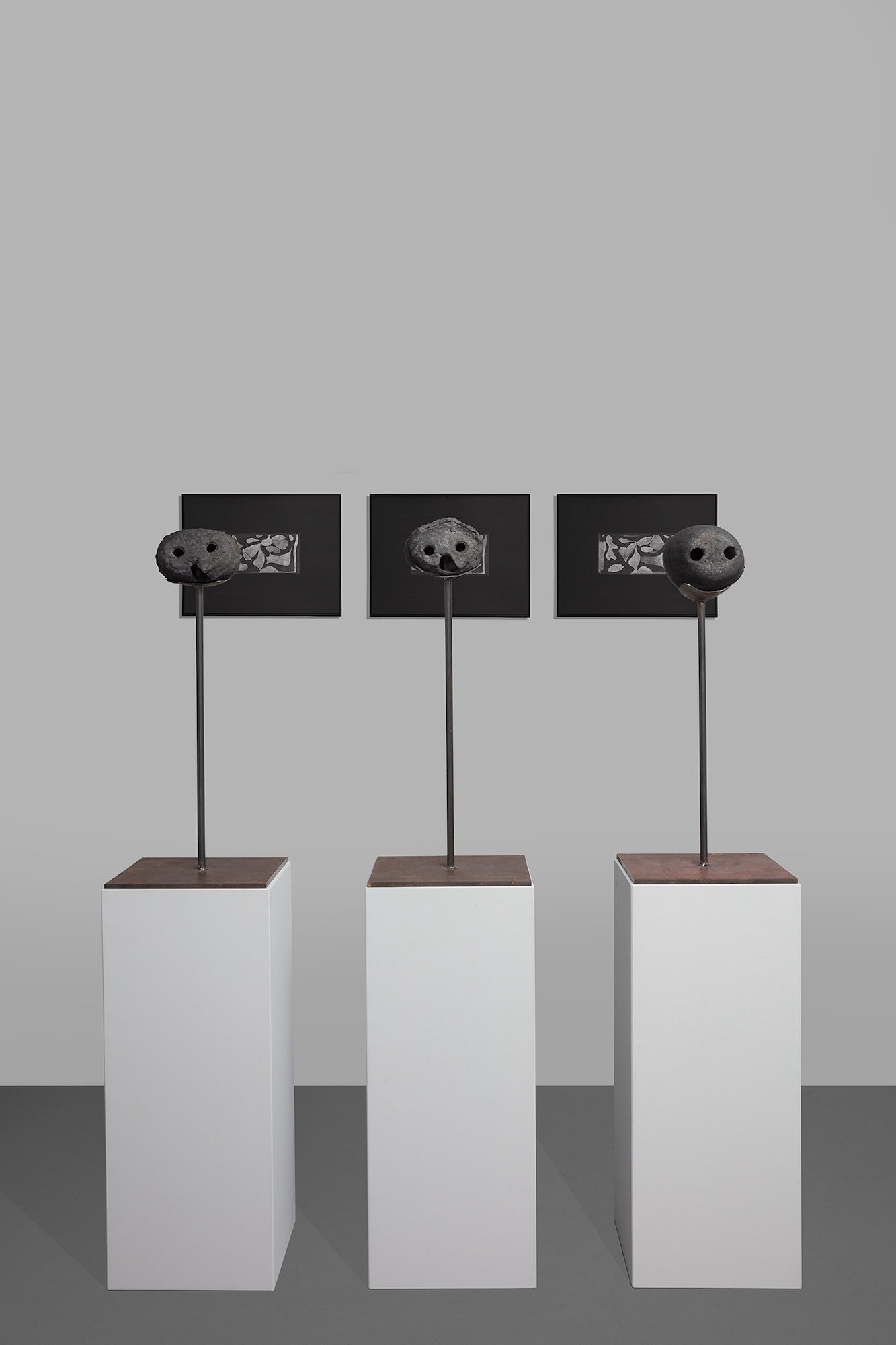

Con un’estetica e un approccio differente anche i lavori di Giovanni Fredi, “Maschera 01, 02, 03”, e “untitled (series)” sembrano arrivare dal passato, ma creando un corto circuito, tra il segno, la forma, le modalità di rappresentazione e la loro significazione. Le “maschere” sono visori, realizzati con un materiale “antico” e naturale come l’argilla, potenzialmente funzionanti e le immagini, paesaggi generati da IA, ma formalizzati con una stampa fotografica ai sali d’argento in formato equirettangolare. Oggetti semplici, resi complicati, sofisticati, diventano punti di ancoraggio del reale.

Stefano Spera con “Variations (Hermes, THE NET)”, ritorna nello spazio di SMDOT/Contemporary Art con una variazione di una sua opera già esposta alla fine del 2021. La ricerca attraverso l’utilizzo di un programma che utilizza l’IA è disattesa, “The Net”, non corrisponde all’opera reale, quella rappresentata ed esposta precedentemente. A questo punto Stefano grazie alla pittura evidenzia e fissa l’errore, resistendo al verosimile, non accontentandosi ed “indicando” il vero.

Eleonora Roaro, con il video “Pallas’s Cat There Is a Picture in My Head” e Federico Poni con l’installazione “For You (Automatic) Information” decidono, con punti di vista, procedure, atteggiamenti dissimili, di occupare, di abitare questa nuova tecnologia, non solo di utilizzarla.

Eleonora con grande ironia “provoca” le conoscenze della IA riguardo ad una specie particolare di gatto, gatto di Pallas, star del social media Tik Tok ed all’idea di desiderio. La poesia ottenuta diventa a sua volta pretesto per la generazione di un brano musicale, sempre da parte di un programma che usa l’IA. Eleonora si appropria di tutto il materiale, lo interpreta e lo presenta come video musicale che segna il suo debutto come cantante con la creazione di una Hit invernale. Siamo sicuri ci sia solo questo nel video? Una canzone, una storia di un’amica che vuole a tutti i costi adottare un gatto selvatico in via di estinzione, oppure qualcosa di più misterioso, complicato, umano?

Federico si cimenta in una performance, interagendo e registrando le reazioni, le risposte, di un particolare programma di IA a un suo racconto. Le sue parole, le sue frasi, i suoi pensieri esposti ad alta voce vengono riconosciuti, interpretati dalla macchina, non sempre in quella che noi riterremmo la maniera giusta. Si creano fraintendimenti nella comunicazione tra l’uomo e la macchina. Errori ed inciampi necessari affinché venga sempre rinnovata la nostra voglia perenne di cercare, svelare la verità.

Guido Segni con “Poor White Guy Can’t Help but fall asleep”, unico lavoro non realizzato per la mostra, immagine stampata su un lenzuolo e tratta dal video “The Han Collection (or how we got wired, tired and fired”, ci ricorda che abitiamo lo spazio che ci circonda attraverso il nostro corpo, che possiamo considerare come uno schermo sofisticato, il quale grazie al suo dispositivo innato della stanchezza riesce a resistere, si finge morto, ma si è solo addormentato, sta recuperando le forze per affrontare la complessità del molteplice, supportato dalle nostre invenzioni tecnologiche senza mai smettere di interrogarci sul loro funzionamento e continuando a surfare dando forma alle nostre “tecnoutopie” tra desiderio e bisogno.

Stefano Monti

SMDOT is proud to announce the beginning of its fourth year of events by presenting the group show “SURFING ON THE ALGORITHMS”. Seven Italian artists, Marco Cadioli, Alessandro Capozzo, Giovanni Fredi, Federico Poni, Eleonora Roaro, Guido Segni and Stefano Spera, have created previously unseen works (or almost unseen). They explore the intersection between technology and creation, looking at the very topical theme of artificial intelligence, and in particular at its fundamental element, algorithms.

AI was until recently confined to research laboratories and has only made its disruptive entry into everyday life in recent years. Everyone seems obsessed and fascinated by its uses and its promises of seemingly endless growth and development, as well as by the possibilities for the application of an increasingly efficient and pervasive technology.

The title of this text, “Neither intelligent nor artificial” may sound provocative, it may seem like a negative judgement a priori on technology, AI and algorithms, but in fact it is just a bit of hyperbole hoping to attract your attention and draw your gaze towards a particular point of view.

We are often too charmed by these machines and software, we proclaim their intelligence on the basis of the results we manage to obtain. We are astonished by the images presented to us as a result of a request entered via text, or by a text written about a topic we submit, even the crafting of a poem, a song or a piece of music, again upon specific request. Interestingly, should we not be satisfied, the machine will continue to look for solutions for us, without ever getting tired – or almost. It will always try to please us. It answers will always be plausible.

Artificial Intelligence is the simulation of human intelligence in machines programmed to think and learn like humans. Artificial intelligence systems can perform tasks such as understanding natural language, recognizing images, making decisions and solving problems. There are different approaches, but they all involve using advanced algorithms and mathematical models to process and analyse the data. Some of the principal approaches are based on systems with a set of predefined rules for making decisions and solving problems. In a nutshell, AI is a branch of computer science that deals with creating machines or computer systems capable of performing tasks that would normally require human intelligence. It uses advanced algorithms and mathematical models to process and analyse data and make predictions or decisions based on them.

This means that somehow they give us the illusion of finding simple solutions to our doubts or expectations, but only we can decide if those solutions satisfy us or not. The way these systems learn and fulfil our desires is based on deception, an approach very common among humans, but also among animals and plants.

We are accustomed to living with what we might call trivial deception: something that we know is not real, but that in certain circumstances, we instinctively decide to consider as such.

Arguably, the history of thought is born and based on deception. The Sophists, Plato’s metaphor of the cave, the invention of myths, religions, the invention of perspective, scientific discoveries, literature, the photographic image, cinema, advertising, TV series, social media, Siri, Alexa, etc…

Human beings have always been attracted by illusion and deception, it is part of their essence, their vulnerability and their modes of relationship. At the same time we had to develop skills to protect ourselves from it, to try to recognise it in advance and not fall for it.

Somehow we are going back to the initial hyperbole: the problem is not artificial intelligence and its ability to design machines that are capable of better performance than human beings, with all the positive and negative consequences on human habits and all the ethical and social implications, rather, the problem is on our ability and desire to distinguish between humans and machines. Refusing to interact with AI is out of the question, but we can resist. We can keep a balance, like in surfing, between the use of the tools available through AI to our benefit, and adopting an informed, critical, sceptical, creative attitude towards it. The challenge is becoming a sophisticated user.

In this, looking at art and art works can be an excellent exercise in not forsaking complexity, sophistication, difficulty and dissatisfaction.

From this point of view, “SURFING ON THE ALGORITHMS” is a sophisticated, complex and uncomfortable exhibition, every single work is a threshold of meaning for the viewer, every work brings with it many questions, every work is lacking a definitive answer despite its aesthetic definition. The conceptual dimension that unites all the works is research into the type of images that we are being produced in the contemporary, also through new technologies, and questioning what representation of reality we want to build with them.

Marco Cadioli’s installation “ CURATING THE AI” is the creation of the documentation of an art exhibition, with artists, artworks, an opening event, performances and cultural events and visitors, all through an AI-based program. Everything was documented and published on the net, to great appreciation by the public, curators, critics and artists, only with some being disappointed for not having been invited. This has generated a trivial deception. The documentation of his exhibition, through digital prints on dibond and digital polaroids, participates as a work of art in the group exhibition, it becomes a performance that took place at another time and in another space, it becomes a meta-exhibition, or a meta-art work. The chronological representation of time is changed. A sort of future in the past.

There is also this kind of future in the past in Alessandro Capozzo’s works. In “Chimera I, II, III, IV”, we are attracted by images that seem to come from some museum of natural sciences from the past, or from an 18th century collector’s Wunderkammer. Lyrical, plausible images which are reminiscent of the features of plants and animals, without being either one or the other, offer us a metaphysical representation of past elements that come from the future.

With a different aesthetic and approach, the works of Giovanni Fredi, “Mask 01, 02, 03”, and “untitled (series)” also appear to come from the past, but create a short circuit, between the sign, the form, the modes of representation and their meaning. The “masks” are potentially functional face coverings, made from clay – an “ancient” and natural material – and images: landscapes generated by AI, but formalised with a photographic silver salt print in an equirectangular format. Simple objects are made complicated and sophisticated and become anchoring points of what is real.

Stefano Spera’s “Variations (Hermes, THE NET)”, marks the artist’s return to the SMDOT/Contemporary Art space with a variation of one of the works he exhibited at the end of 2021. The search through the use of a program that uses AI doesn’t bring the promised results: “The Net”, does not correspond to the real work, the one previously represented and exhibited. At this point Stefano both highlights and fixes the error through painting, resisting the plausible, not just being satisfied with “indicating” the truth.

Eleonora Roaro’s video “Pallas’s Cat There Is a Picture in My Head” and Federico Poni’s installation “For You (Automatic) Information” take the stance of occupying and inhabiting this new technology with points of view, procedures and different attitudes, not just using it.

With great irony, Eleonora “provokes” AI knowledge about a particular species of cat, Pallas cat, a Tik Tok star and the idea of desire. The poetry generated becomes in turn a pretext for generating a piece of music, always by a program that uses AI. Eleonora appropriates all the material, interprets it and presents it as a music video that marks her debut as a singer with the creation of a winter hit. Are we sure that’s all there is in the video? Is it just a song, the story of a friend of hers who wants to adopt an endangered wild cat at any cost, or something more mysterious, complicated and human?

Federico engages in a performance, interacting and recording the reactions and the responses of a particular AI program to his story. His words, sentences and thoughts are spoken and recognised, interpreted by the machine, not always in what we would consider the right way. Misunderstandings are created in the communication between man and machine. Mistakes and stumbling blocks are necessary so that our perennial desire to seek and reveal the truth is always renewed.

Guido Segni’s “Poor White Guy Can’t Help but fall asleep”, the only work not made specifically for the exhibition, is an image printed on a bed sheet, taken from the video “The Han Collection (or how we got wired, tired and fired”. It reminds us that we inhabit the space that surrounds us through our body, which can be considered as a sophisticated screen. Thanks to the innate device of fatigue, our body manages to resist: it pretends to be dead, but it has only fallen asleep, it is recovering the strength to face the complexity of manifold reality, supported by technological inventions without ever wondering about their operation and continuing to surf, giving shape to our “techno-utopias” between desire and need.

Stefano Monti